How to Fund and Grow Your Canadian Startup

We wanted to uncover common elements in the fundraising strategies of “successful” Canadian high-tech startups that may have contributed to their success. For example, were all these companies part of an elite network? Were they formerly connected to influential industry leaders?

To arrive at this information, we spent months analyzing hundreds of thousands of data points across four different databases. We also spoke with key stakeholders, including VCs in both Canada and the US, select Canadian companies, and industry thought leaders. Through this research, critical insights were gained which have never been published before―insights we’re passing along to you to help increase your chances of being the next Canadian success story. And although the focus of this piece is largely on Canadian startups that have been involved in an M&A transaction, it is believed an analysis of the IPO market would lead to similar conclusions.

To arrive at this information, we spent months analyzing hundreds of thousands of data points across four different databases. We also spoke with key stakeholders, including VCs in both Canada and the US, select Canadian companies, and industry thought leaders. Through this research, critical insights were gained which have never been published before―insights we’re passing along to you to help increase your chances of being the next Canadian success story. And although the focus of this piece is largely on Canadian startups that have been involved in an M&A transaction, it is believed an analysis of the IPO market would lead to similar conclusions.

At the core, our findings pinpoint that Canadian company success is closely correlated with their breaking outside of their regional boundaries and getting closer to their end markets. In most cases, this happens to be the US.

PART I

Since the World Wide Web has no borders, it’s easy to think that an Internet-based business can target any world market regardless of where that company is located. Unfortunately, more often than not, this is a myth. As one Toronto VC told us, “As Canadians, we feel we are close enough to the US that we can still operate out of Toronto and cater to the American market. I don’t believe this to hold true. A company’s odds of success are better the closer they can get to their market.”

Stephen Hurwitz, a partner at Choate law firm, has written and spoken extensively about the Canadian venture capital industry. In many cases, he advises entrepreneurs to be physically in the top markets to which they sell.

Another way startups can get close to their end markets is through their investors. One of the biggest complaints Canadian entrepreneurs have, when launching and growing their startup, concerns the “lack of venture capital dollars available in Canada.” Right away, this is the wrong attitude to have.

We live in a borderless world, so from the get-go, look outside your immediate area for funding. Don’t just look for any fund or John Doe to cut you a cheque. Be strategic, and think about which angel investor or venture capital firm has the best industry knowledge and expertise to help build your company the fastest. Consider which investor can help you best execute on your company’s go-to-market strategy, and which investor has the strongest connections with channel partners, end customers and even potential acquirers.

If a VC that knows your company’s sector well rejects you, ask them for a debrief to understand why. This could yield key insights, so don’t dismiss it. They may have seen a dozen or so other companies doing exactly what you’re trying to do, or they may recognize the lack of unique value your company provides.

Finally, while it may seem easy to rely on local Canadian VCs to connect you with the right investors in the Valley, keep in mind that often they won’t stretch themselves to leverage their relationships for you. Ultimately, it’s up to you―the entrepreneur―to bring the right investors on board early on.

The following sections shine light on who these “right” investors may be and why they can make the difference between a startup that stalls and one that succeeds.

CANADIAN VS US STARTUPS

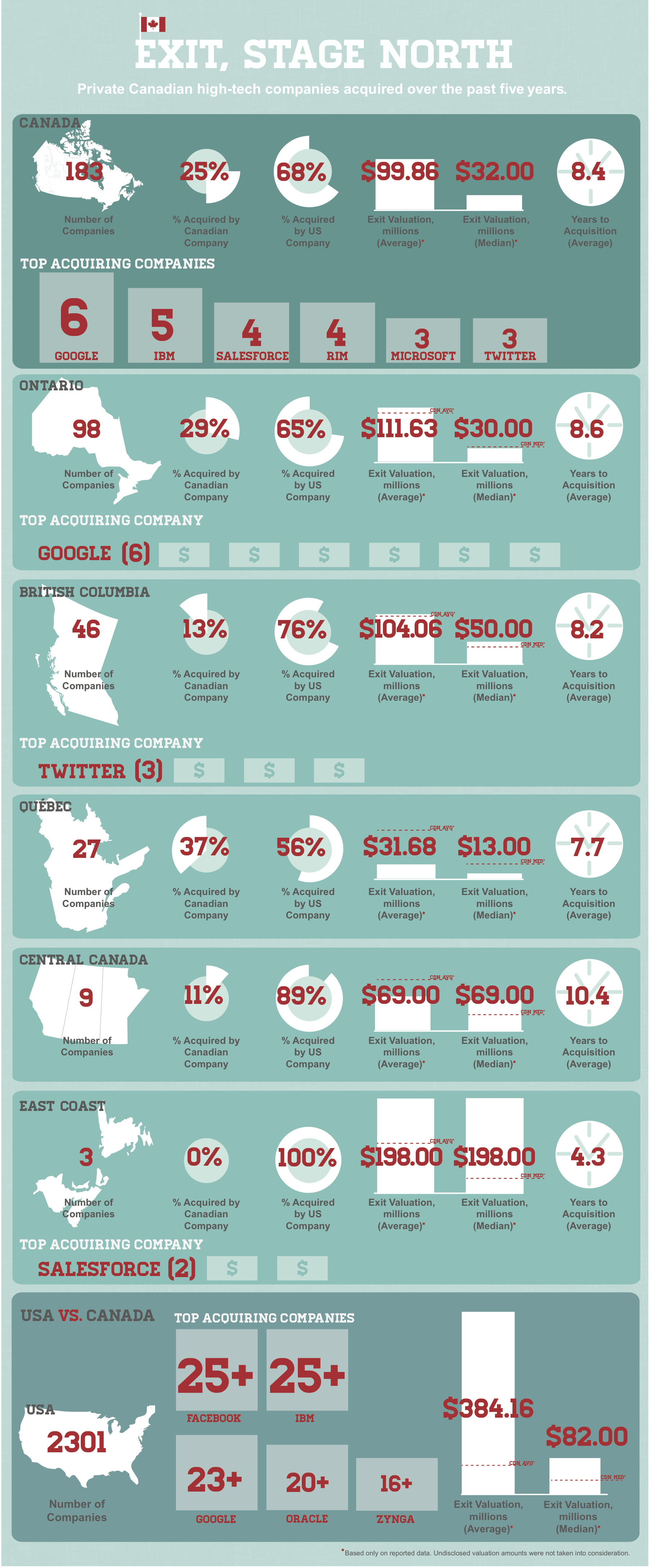

To set the stage, it’s helpful to understand the state of the technology industry in Canada today. The following infographic presents data on Canadian high-tech companies acquired over the past five years. This data was culled from a combination of both public and private sources, to understand company valuations, average time to acquisition, and acquirer locations.

What is striking about this data? Consider this:

• 183 high-tech Canadian companies were acquired over the past five years, versus 2,300 US companies. Compared to Canada, the volume of acquisitions in the US roughly aligns with the 10:1 ratio that is often applied to assess trends between the two countries.

• Of these 183 Canadian companies, nearly 70% were acquired by US corporates. For existing Canadian startups, this begs the question: if your ultimate acquirer is likely to be from the US, then how are you going to bridge that gap to liquidity?

• The average number of years to acquisition was approximately eight.

• The average exit valuation for Canadian companies was approximately US$100 million, compared with a US company valuation of US$384 million. Median values were $32 million and $82 million respectively.

This last point is often an area of contention, as industry experts grapple with why Canadian companies are valued less than their US counterparts. Industry experts point to the fact that Canadian companies sell out too early, before they have a chance to grow into larger, global businesses.

he cause of this could be a lack of late-stage financing available in Canada to help fuel companies’ growth. Which is why most of the companies that have only Canadian investment are sold at a relatively young stage, hence the smaller valuations.

Another reason could be a Canadian mentality to not think “big” in the early days. As one Toronto-based VC told us, “Young Canadian entrepreneurs constantly worry about dilution, instead of making growth their focus. My advice to them would be to take in as much money as they can early on, and focus on growing the pie instead of worrying about giving up the pie!”

From a regional perspective, the following stands out:

• 76% of acquisitions in British Columbia were made by US corporates, versus 65% and 56% in Ontario and Quebec, respectively. It appears that the farther a company is from the west coast (or Silicon Valley), the lower its odds of being acquired by a US corporate. Could something as simple as the cost of travel be deterring Valley-based companies from frequenting Toronto and Montreal?

• While Quebec-based companies had the highest rate of acquisition by Canadian corporates, they also had the lowest exit valuations.This indicates Canadian corporate purchase prices are much lower than those of US corporates.

• All six of Google’s Canadian acquisitions were made in Ontario. This is where two out of three of Google’s Canadian offices are located.

• All three of Twitter’s Canadian acquisitions were made in British Columbia. With companies like HootSuite blossoming, we can’t help but wonder if Canada’s west coast is becoming a hub for social media talent and innovation.

As seen through this data, the US plays a big role in driving Canadian company exits.

PART II

While we know US corporates are driving the majority of Canadian company exits, it is helpful to understand how Canadian ventures are actually attracting the attention of these acquirers. Is it through strategic relationships―or is it, as we believe, through a company’s investors?

To examine this, we looked at the 23 VC-funded high-tech Canadian companies that had been acquired in 2012. Of these companies, 65% had received non-Canadian investment prior to acquisition, and 57% had received investment from US VCs.

This reinforces the need for Canadian companies to look to the US for late-stage financing. It also presents a possible correlation between obtaining US investment and ultimately being acquired.

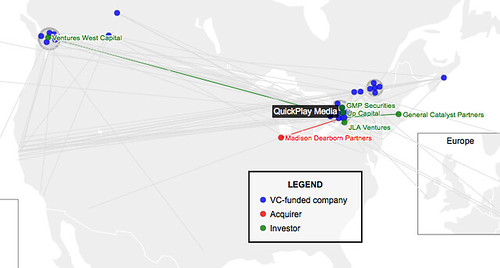

This data visualization maps the 23 companies, along with their respective investors and acquirer. The map was created with the aim to help illuminate what connections may have led to a company’s acquisition.

The map makes clear some important insights:

• 19 companies were bought by non-Canadian firms, of which 13 companies (or 68%) had obtained investment from VCs located in close proximity to their acquirer.

• Ottawa’s Blaze Software raised money from two Boston-area investor groups, only to be sold two years later to Massachusetts-based Akamai Technologies.

• Waterloo’s BufferBox obtained seed funding from both Y Combinator and Google Ventures, having made their initial connection with Google during a Communitech event. A short time later, the company was acquired by its early investor, Google. This was only the second time Google has purchased a Google Ventures portfolio company.

• Toronto-based Dayforce was acquired by its early investor and distribution partner, Ceridian.

• Halifax-based GoInstant was acquired by Salesforce one year after receiving investment from several US VCs. One of these VCs was Greylock Partners, whose investing partner, Reid Hoffman, is the founder of LinkedIn.

• Localmind, based in Montreal, was referred to Year One Labs by former GoInstant VP and Year One Labs founder, Ben Yoskovitz. Shortly thereafter the company raised money from several Canadian and US VCs and was eventually sold to Airbnb.

• Vancouver’s Context Media Solutions obtained seed funding from Valley-based Accel Partners, only to be acquired two years later by Twitter.

In conclusion, location matters. These few examples illustrate the connection between a company’s investors and its end acquirer, which is that in most cases the two parties are located in close proximity.

This data also proves the importance of developing the right relationships early on, and, more importantly, just how critical it is to have the right VCs to enable your company exit.

PART III

In evaluating US VCs, it’s important to identify whether they hold any Canadian investments, as many firms have criteria about the geographic areas in which they will invest. Chances are that if an established VC has not previously invested in a Canadian company, they are not likely to do so in the near future.

It’s the same reason why most Canadian VCs do not invest in England. It’s just not their focus. Keep this in mind when beginning your search.

This infographic highlights the top 10 US firms investing in Canadian technology companies. It helps to dig down a bit and examine what drives these firms to invest north of the border.

For Bridgescale Partners, its 13% Canadian portfolio can be attributed to Canadian and C100 charter member, Rob Chaplinsky. Rob recognizes the recent proliferation of new ventures in Canada over the past few years and feels the startup landscape is growing into something “incredible.”

This growth brings Bridgescale to Toronto and Waterloo frequently, to chat with companies and keep its finger on the startup pulse. We asked Rob why other US VCs don’t frequent Toronto as they do New York or even Boston. He feels proximity is the main issue, recognizing that a last-minute flight from the Valley to Toronto averages about $1,400.

Location-wise, Vancouver has a significant advantage over Toronto as it is closer to the Valley. We know of at least one US VC intending to establish a Vancouver office for this exact reason.

Having a Canadian on the team also drives Newbury Ventures to invest in Canada. Partner Ossama Hassanein is a University of British Columbia graduate and a current C100 board member. At Greylock Partners, former partner Charles Chi is a Carleton University alumnus, as is Y Combinator partner Trevor Blackwell.

Whether Canadians at US VC firms intentionally evaluate Canadian opportunities, or stumble across them during visits home, it’s obvious that their presence significantly affects their firm’s investment in Canada.

Some VC shops like Bessemer Venture Partners and Intel Capital have a truly global investment strategy. Bessemer invests nearly 25% of its funds outside of the US; for Intel, this percentage is closer to 50%.

Accelerators such as 500 Startups and Y Combinator attract large numbers of early-stage Canadian companies looking to be part of an elite accelerator cohort. 500 Startups visits Canada often to promote its program, with Dave McClure and Paul Singh frequently appearing at events, meeting with teams and hosting talks.

NEA and Sequoia Capital are two of the most prominent VC firms in the world. They are pushed to invest around the globe in order to deploy all their capital. Moreover, NEA has invested in syndicate with several Canadian VCs, including OMERS and Relay Ventures. NEA stays abreast of promising investment opportunities north of the border by exchanging deal flow between interested parties, without actually setting up a team on the ground.

Some observers feel US investor activity in Canada has generally been slow due to a former Canadian tax rule known as Section 116, which made it very expensive and time-consuming for US VCs to invest in Canada. In 2010, that rule was reformed so that it no longer posed an impediment to foreign VCs seeking to invest in Canadian companies.

However, as Stephen Hurwitz explains, “the Section 116 reform hasn’t necessarily caused a flood of US investors coming north of the border, as many have been distracted by their struggles in fundraising and in keeping their late-stage portfolio companies alive during a weak IPO and M&A market. But, as the markets come back, the Section 116 reform will have a favourable impact on Canada’s startup community.”

Also spurring investors to come north is the new Canadian startup visa, which entices firms to explore setting up shop in Toronto or Vancouver. The startup visa’s purpose is to attract overseas opportunities here, given getting a company into the US is a difficult process.

Hurwitz, who has met with various US VCs investing in Canada, finds many of them love doing Canadian deals. “What they see is a combination of fabulous technology, high-quality and lower priced tech-talent, less competition for deals, and better pricing.”

Their challenge, however, often revolves around finding the right management team. As Chaplinsky tells us, “There are not a lot of people who can scale $10 million revenue companies. This type of talent isn’t at a Blackberry or even at a Google. It’s about finding very good managers, very good strategic planners and very good operations people. Unfortunately, in Canada today, these people are very rare.”

PART IV

Along with the strategic value that US venture capitalists add to a company, Canadian VCs add their own distinct value.

In terms of de-risking opportunities, Canadian VCs work as a great filter. Various Canadian firms have even developed relationships with US VCs, and act as a feeder by sending deals south of the border. When seeking investment, is it not a bad idea to ask your Canadian VC what US contacts or inroads they have. Ultimately, if your company wants to thrive in the larger north-south playing field, these connections will be critical.

Moreover, there have been many instances when a US firm is interested in investing in a Canadian company, but wants a local VC (in the company’s city) to be actively involved. This is another area where Canadian VC firms can add strategic value.

The Canadian venture capital industry is relatively young, having only reached a critical mass of investor groups and entrepreneurial startups in the late 1990s. In contrast, the US VC industry has been growing since as early as the 1950s. As a result, the Canadian VC industry is experiencing its own set of growing pains, which has important implications for companies looking to raise money.

CHALLENGE ONE: FOLLOW-ON FUNDING

Over the past few years, Canadian technology startups secured, on average, less than 50% of the funding of their US counterparts. Later-stage companies in Canada have struggled even more, garnering only one-third of what comparable US firms raised. These trends have several implications, both for young and fast-growing companies.

First, many high-potential companies are being forced to slow growth because they simply cannot access the funding necessary to compete in a global economy. Additionally, a lack of funding prevents Canadian companies from attracting the top talent and leadership necessary to evolve their businesses and sustain a significant competitive advantage.

Second, Canadian companies are being sold too early and, in many instances, too cheaply, mostly to US buyers. This statistic is reflected in the Exit, Stage North Infographic, which shows that US corporates have been involved in nearly 70% of Canadian company acquisitions, and that the average valuation for a Canadian company was $100 million, compared to $384 million in the US.

Third, faced with a scarcity of local funding, many Canadian startups, particularly the late-stage ones, look south for financing. In a recent report by Thomson Reuters Canada, foreign investment in late-stage firms has been, on average, three times larger than domestic investment.

This may not present a challenge for the startups themselves, but it certainly has negative implications for Canada’s VC industry. As Stephen Hurwitz relates, “Canadian VC players often get diluted in late-stage financings, since many can’t play in these rounds. In a prior period in which US firms invested in 10% of Canadian VC deals, they accounted for 31% of exits and 44% of all exit proceeds. This is problematic for Canadian VC firms, and for the overall health of Canada’s VC industry.”

The good news is that the Canadian government has proposed a plan to pump $400 million into the investment community, which will hopefully lead to more late-stage VCs who can fund the full lifecycle of a company. Through this money, the federal government hopes to generate at least another $600 million in private funding from both US and Canadian limited partners.

Interestingly, only a third of the money raised will need to be invested back into Canada. This is based on the notion that we live in a borderless world and that if Canada does not create relationships with top VCs the world over, then we deny Canada access to them as well as the knowledge and connections they bring.

Moreover, if we don’t invest in the best companies around the world, as well as the best companies in Canada, then we will lose the opportunity to enhance our ROI. This approach is an effort to help revitalize the Canadian VC industry. In Hurwitz’s view, “it is a far-sighted plan and, while no plan is perfect, it’s in my opinion one of the most progressive that any country has ever devised. The government deserves a lot of credit because politically this is hard to do.”

CHALLENGE TWO: EXPERIENCE AND SECTOR DEPTH

In Canada, 92% of venture capital firms were formed after 1994. In contrast, the US has firms that have been around for over five generations, enabling them to have considerably more hands-on experience.

In the US, big funds will spend millions of dollars analyzing gaps in each area of ICT, and then they will go find a company to fill it. This sector expertise is something many of the US firms develop as part of their investment strategy. For example, you will find firms in Boston with deep expertise in healthcare IT and Silicon Valley has firms focused purely on big-data startups.

Unfortunately this level of expertise is just not possible for many Canadian VCs because they don’t have the bandwidth due to their small size and there are not enough local deals to focus in on one sub-sector of ICT. As a result, Canadian VC firms traditionally become generalists, where they work to understand the problem that a specific technology addresses, rather than trying to find an innovative technology that can solve a pre-identified problem.

This lack of sector expertise can make it difficult for Canadian VCs to pull a company along, as they do not necessarily have the critical industry insights to help a startup grow.

CHALLENGE THREE: QUALIFIED TALENT POOL

By looking at the credentials of those working at some of the top US venture firms, it’s clear that most of them are former entrepreneurs who successfully exited companies and went on to join the venture world. This happens less in Canada, as we don’t have as many former successful entrepreneurs.

At Canadian VCs, the majority of the talent has either some industry expertise or are ex-bankers. As one Canadian VC tells us, “I worked in corporate finance for many years, and many of my colleagues from that time are now working in venture funds. But they have never run a company. That would not fly in Menlo Park.”

As for the Canadian entrepreneurs that were successful, the majority happened to live in or have now moved to San Francisco. In fact, it is believed that there are more Canadians working as general partners in San Francisco venture funds than there are in Canadian funds.

The solution? According to one Canadian VC, “Canada as a whole needs to be more cognizant of how we’re training talent. Silicon Valley wasn’t successful overnight. It took years of mistakes and proper training to reach the critical mass of talent they have today.”

One possible training program is the Kauffman Fellows program, a two-year fellowship dedicated exclusively to serving junior associates at venture firms. Individuals from around the world fly into Palo Alto through the two-year term, to meet with others in their peer group, share best practices and learn directly from some of the top folks in venture capital.

These connections carry on well past the duration of the program, which now connects venture capitalists across six continents. While an invaluable program, Kauffman Fellows is also expensive and can run upwards of US$60,000 per individual.

This cost may not seem much for some of the large US venture firms, but it is a stretch for some of the small Canadian firms. However, without this training, Canadian firms will continue to miss out on developing strategic global relationships and industry expertise.

The UK venture industry was in a similar predicament, and in 2006, the UK’s Department of Trade and Industry stepped in and subsidized the training costs for junior talent across many of their local VC firms. Today, 10 Fellows (or 3% of all Kauffman Fellows) reside in the UK, the majority of whom remain in the venture capital industry.

The young talent today are the future leaders of Canadian venture capital firms, and in order to get them competing on the same level as their US and global colleagues, we’ve got to give them access to the same resources. This will also help mitigate the loss of top talent to the US.

In summary, Canadian venture firms can add real value to early-stage companies, provided the VCs have the right industry expertise and partnerships in place to help guide a company, and make the necessary connections to help it grow.

PART V

If Canadian companies are being encouraged to look outside the country for investment dollars, then it’s important to understand the impact this will have on Canada’s high-tech industry.

Intuitively, it may seem that encouraging foreign investment would result in a loss of talent and innovation for Canada. However, our research suggests otherwise.

Perhaps the best data to highlight the benefits of foreign investment in Canadian companies comes from the Israeli model―a strategic initiative undertaken by the Israeli government to foster the creation of Israel’s startup and venture capital industry.

Prior to 1993, Israel had almost nothing in the way of a startup or VC community. That is, until its government set aside $100 million to attract experienced and international VCs to the country. From there the startup model took shape. Today it is largely based on:

• Startups being market driven, not technology driven. They work with customers from the very beginning to ensure that products are properly targeted.

• Startups obtaining strategic investors early on, sometimes as early as the A round. Today, over 75% of an Israeli company’s funding comes from investors outside the country.

• Going global from day one. Once a company reaches a market-ready stage, the sales and marketing teams relocate to a country that is a key market. Oftentimes, it is the US.

Today, Israel has the third-highest number of companies listed on the NASDAQ, behind the US and China. And it is ranked number two in terms of venture capital availability, second only to the US.

Many Israeli-based VC firms are offshoots of American VCs, such as Bessemer Venture Partners and Battery Ventures, who have established local investment teams. Additionally, there are some 220 international funds that actively invest through an in-house specialist.

Since the 1990s, Israeli VC assets have risen sixty-fold, from under $100 million to $3 billion; in 2012, a total of 575 high-tech Israeli startups raised nearly $2 billion. Compare this with the $1.5 billion raised by 395 Canadian startups in 2012, keeping in mind that Israel has one-fifth the population of Canada.

Israel didn’t achieve all this success by telling companies to stay local. Rather, it advised them to get out and follow their markets. Israel’s experience is evidence that Canadian companies can and should do the same.

As Hurwitz notes, “Once Israeli companies became highly successful, money flowed back into the country to further develop the venture capital industry. And R&D infrastructure was further developed when global technology companies located facilities and expanded existing facilities in Israel.”

THE RIGHT TIME

Knowing when to look to the US for investment can be difficult to assess, and it often depends on the stage and nature of the company itself. However, one VC we spoke with advocates strongly that a company get at least one tactical investor early on (i.e., an investor with the right industry connections and expertise).

“The myth is that you raise seed money in Canada and later rounds in the US,” he said. “But I think that becomes too late for companies, because they won’t get strategic advice or clients soon enough. Companies should think about how to bring the most value to their teams as early as possible.”

However, companies need to be aware that there are important grant and tax implications when seeking early US investment. This is particularly true for the SR&ED program, which is significantly diminished, if not eliminated, when there is foreign control.

Whether or not these penalizations will be lifted is yet to be seen, but as Hurwitz sees it, “SR&ED should be agnostic as to where a company’s investment comes from. After all, the government wants the best VC firms in the Valley, Boston and New York to invest in Canadian companies, so it’s not reasonable to penalize a company for obtaining significant financing south of the border.”

TEAM LOCATION

Sales and marketing: the best-case scenario for a Canadian startup is to locate its sales and marketing teams in the target market. If you were selling to the US government, for example, you would want your lead salesperson to be in Washington, DC and not in Guelph, Ontario. And ideally, you would want to recruit this sales lead from that area as they would know the market best.

Research and development: With respect to R&D teams, the evidence suggests startups should keep these in Canada. Having the R&D teams remain in the home country is the path many Israeli companies followed, and it proved the most effective outcome. Doing so helps Canada flourish in terms of job creation and industry growth. As Hurwitz sees it, “At some point more leading global tech companies will decide they want to build their next plant in Toronto, Montreal or Vancouver, rather than in Israel, due to Canada’s outstanding talent.”

In short, by encouraging US or overseas investment, Canada will not necessarily lose key talent and innovation. Rather, Canada will benefit from a richer and more developed startup industry.

This content was originally published on MaRS.