How Much Longer Will We Tolerate the Outrageous Cost of Television?

I’m not a good advocate for commercial television.

I’m not a good advocate for commercial television.

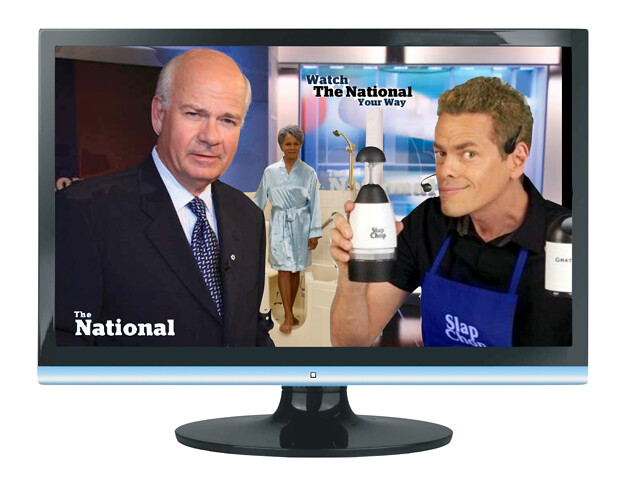

Over the past decade I have gradually weaned myself off all programming with the exception of the CBC National, which, in spite of my affection for business correspondent Amanda Lang, is also becoming difficult to tolerate. Given that I am edging towards the demographic that supposedly admires “commemorative coins” and the marvel of the “walk-in bathtub,” I have to wonder why I have become so irritated with the solicitations I am forced to endure in order to remain an informed Canadian?

Who am I to complain about a service that is being provided to me “free” of charge?

The average Canadian wage is $46,000 a year—$883 a week or $22 an hour. The average hour of “free” broadcast television has 15 minutes of commercial interruption, which is the accepted price that viewers pay for the privilege of watching.

That means that ostensibly “free” TV costs the average Canadian wage earner about $5.50 an hour to view—making it more expensive than the cost of an average 90 minute feature film on iTunes. To add insult to injury the more money one makes and the more precious one’s time is (especially as one becomes older) the more costly commercial TV becomes.

Perhaps this is why I have become so resentful of Mansbridge and company, not for any personal reasons, but because I am forced to endure mindless gibberish in order to watch them deliver the evening news. This is a gross impingement that wastes 25% of my time. And as Ms. Lang will attest, time is money!

So how did this folly transpire in the first place? Who chose this insane and inane model—one that invades privacy, wastes time, and subjects the average Canadian adult to over 14,000 minutes of commercials per annum?

Was it some evil genius or some clever ad-man who conceived of it to sell goods many people wouldn’t otherwise want, much less need? It was neither! If one looks at the problem historically, the entire commercial broadcast model evolved because of technological limitations that could provide no other viable alternative.

In the early days of radio the main economic activity involved the sale of hardware, like transmitters and receivers. There was no means of monetizing broadcast services: artists preformed solely for increased status and public recognition.

By 1921, however, the radio broadcasting monetization issue became an important topic for public debate. Many ideas were floated from Government subsidization through a “national radio tax” to a proposal for “Nickel-in-the-Slot Radio Receiving Sets.” Concurrently, there was no central authority to decide upon nor implement any feasible monetization policy.

In 1922, US Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover convened a three year National Conference on Radio Telephony. The main purpose of the conference was to establish some form of regulation to prevent radio frequency “interference” and to find some economic model to monetize the broadcast industry.

By 1924, the conference had the matter of interference resolved through the careful regulation of licensed “operating channels” broadcasting on non-competing wavelengths. The matter of monetization, however, remained a point of contention. In his final report Hoover wrote:

I believe that the quickest way to kill broadcasting would be to use it for direct advertising. The reader of the newspaper has an option whether he will read an ad or not, but if a speech by the President is to be used as the meat in a sandwich of two patent medicine advertisements there will be no radio left. … The listeners will finally decide in any event. Nor do I believe there is any practical method of payment from the listeners.

An in-depth perusal of the editorials of the day in both the US and Canada indicates that Hoover’s dislike of broadcast advertising was a dead-on reflection of North American public opinion. At the beginning of the Roaring Twenties the general public was appalled at the intrusion of privacy commercial advertising would bring. But as Hoover begrudgingly noted, market forces would ultimately dictate the radio broadcast finance structure.

In February of 1922, two years before Hoover submitted his final report, AT&T had already announced plans to establish a national radio network and sell airtime, which it termed “toll broadcasting.” So the advent of advertising to pay for content “programming” had already begun without government sanction. Although it first began with “a few words from our sponsor” at the beginning and end of a broadcast, “commercials” were soon “interrupting” programs on a regular basis.

From its inception, commercial broadcasting was a model that few seemed to like nor want. But unfortunately there was no viable alternative. It was a model based on the limitations of early wireless technology and, because of the same constraints, it was applied to wireless Broadcast Television some thirty years later.

Fast-forward some 90 years to a time when 25% of Canadian households own PVRs specifically to “time shift” or skip through adverts. With this in mind, it is regressive that broadcasters are now attempting to apply channels, programming, commercials, and other broadcast artifacts to the world wide web—when one great advantage of the Internet is that it provides viable alternatives to monetize motion picture content. In fact, the direct payment model for viewing individual programs and the subscription model for viewing periodical programing would have made complete sense to the fathers of modern broadcasting.

It would seem that today’s broadcast brain-trust mistakenly feel that the flogging of goods and services in the sanctity of ones living room is an inherent right somehow representing the natural order of things. However, they will soon come to the realization that the commercial broadcast model was a compromise to begin with, and people compromise only as long as they believe they have to.

I for one welcome the day when I can pay a subscription fee to watch “The National.” A subscription of perhaps $5.50 per month—rather than the current $5.50 an hour—for intermittent national affairs peppered with enlightened commentary from the likes of slap-chop guy.